Historians and language

It has constantly surprised me that historians seem to take very little notice of the features of the language in the texts that they look at. I did consider enlisting their support and help for the dictionary because it seemed to me that as the people most likely to be reading texts from an earlier period of Australian history they might stumble on and record in their own writing items of Australian English that they discovered. I discovered that they were curiously blind to features of Australian English, even when it affected their own understanding of history.

One notable exception was the historian who wrote to me to ask what kind of drink a casuarina was. This item had emerged in documents from the 1890s. I was able to explain that casuarina was a kind of beer. Apparently a publican in Tasmania had brewed his own beer, flavouring it with casuarina. You either loved it or hated it. It also turned up in South Australia — there was a strong link then between Tassie and Adelaide.

Another historian pointed out to me that in newspaper articles of the 1890s to early 1900s you were as likely to find color as colour, and asked why that was so. This led me to discover the significance in Australia and around the world of the Merriam-Webster International Dictionary published in 1895.

But with these two exceptions there has been silence from Australian historians of the years that I was involved in Macquarie Dictionary.

I was reminded of this as I read a wonderful a wonderful article by Anne-Marie Conde´with the title Ben Chifley’s pipe, published in Inside Story on 9 March this year.

At one point she was talking about Eric Reece and the flooding of Lake Pedder in 1972-73. She commented:

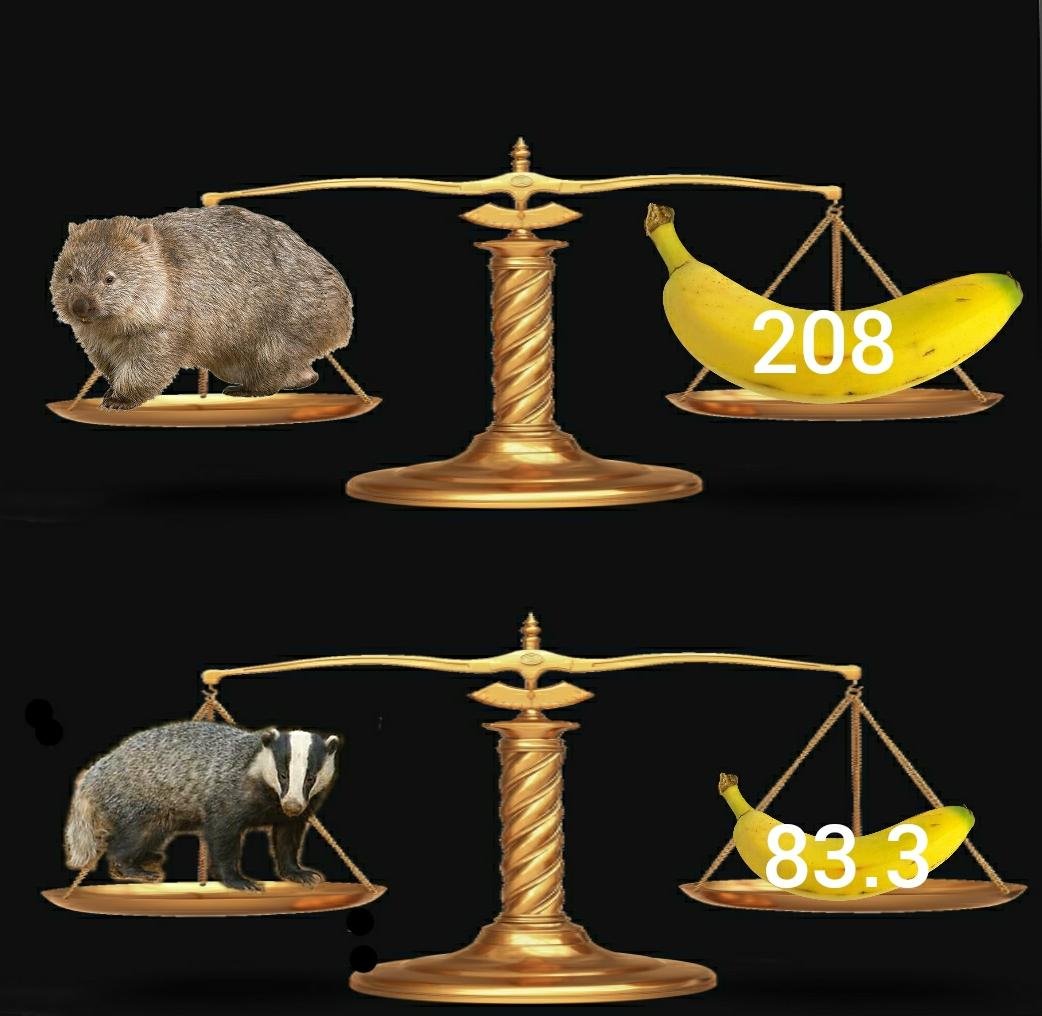

Where some people wept at Pedder’s beauty, Eric Reece was belligerent and autocratic. In 1966 he taunted his opponents with the remark that Tasmania’s southwest contained only “a few badgers, kangaroos, wallabies, and some wildflowers that can be seen anywhere.” (Badgers? Did he mean wombats?)

You would think that this curious reference to a badger in Tasmania would have sent her running to the Australian National Dictionary, online or in print, a reference work that should be by the side of any Australian historian. There she would have discovered that in the early days of settlement the English referred to a variety of marsupial mammals as ‘badgers’ and that in Tasmania the habit stuck, long after the rest of the colony had acquired the word wombat from the Sydney Language. As early as 1831 it is remarked on as being a Tasmanian peculiarity. In 1987 Ruth Park commented that it was a term ‘still occasionally heard in Tasmania’ but then in 2002 there is the observation that, while you won’t hear badger in Hobart, the term is still strong in rural Tasmania.

Rather like porcupine for the echidna. A name for the animal that you will still hear in the bush.

Tasmanians were fond of the badger ham, the hind leg of a wombat smoked in the chimney. And they referred to any makeshift hut or shelter as a badger box. This survived as the name for a portable unit for accommodation and storage, provided to a crew working on the roads.

You get the feeling that, sadly, historians don’t know that the AND exists!